2020 saw highest credit default events since 2009 - what about this year?

In times of crisis the credit default swap market springs to

life. We saw this in the Great Financial Crisis of 2007-2009, the

eurozone debt crisis of 2010-2012 and now the COVID-19 pandemic

that started in 2020 and is still with us. Investors require a

financial instrument that hedges credit risk and protects them

against defaults - CDS is specifically designed for such a

purpose.

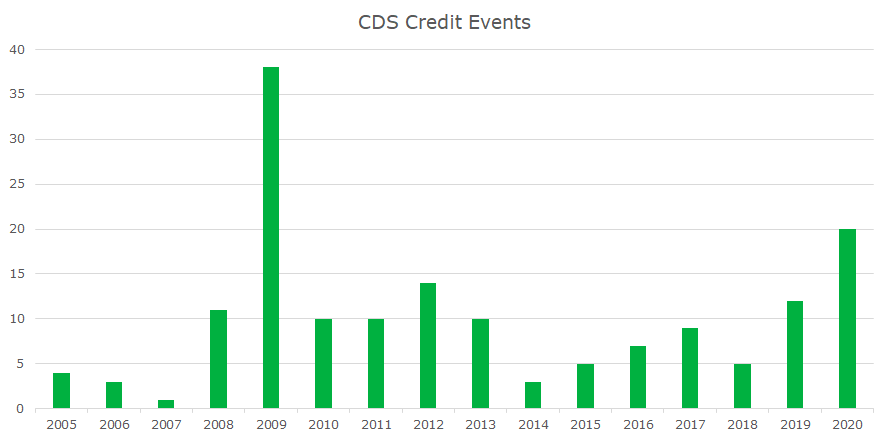

Naturally, we would expect that the number of defaults rose during

2020. And indeed it did. Last year saw 20 CDS credit events across

the globe (including Europcar - auction next month). This is the

highest since 2009 and the second highest since the advent of the

auction mechanism in 2005 (previously all CDS were physically

settled bilaterally).

Source: IHS Markit/Creditex

But there are key differences between 2020 and 2009. First, the

scale: 2009 saw almost double the number of credit events (and the

38 total is adjusted for multiple events across the same company).

Secondly, the type of companies defaulting: 2020 saw multiple US

energy groups triggering events and was the first year that three

sovereigns defaulted (though Ecuador has the dubious distinction of

defaulting in both years). Thirdly, recovery rates were markedly

low: 9 of the 19 auctions held in 2020 produced results of less

than 10.

What does this tell us? It underlines that the recessions of

2008-2009 and 2020 were two very different beasts. The first was a

downturn precipitated by a financial crisis, with a restriction in

credit availability causing defaults across sectors. The recent

contraction was short and focused on specific sectors directly

affected by government lockdowns, alongside weakness in the US

energy sector.

The Great Financial Crisis was the catalyst for a decisive shift in

the Credit Cycle. Since 2009 we have seen the longest expansion

phase in the modern era. In March it seemed that it was coming to

an end and we were entering the downturn stage of the cycle. The

effectiveness of monetary policy was questioned in the face of a

concurrent demand and supply shock. But the world's major central

banks proved that they hadn't run out of ammunition, and their

liquidity support bolstered debt markets and stemmed the tide of

defaults.

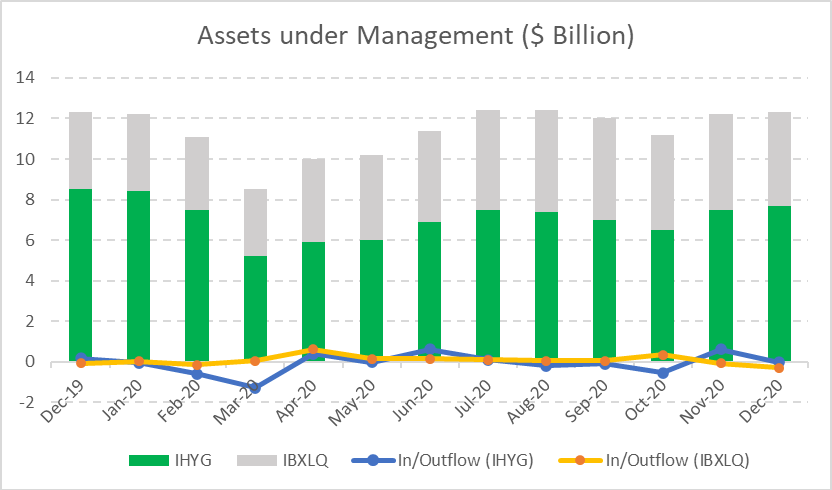

Source: IHS Markit

The markets have confidence that this will remain the case in

2021 - the major CDS indices are now more or less back to where

they started the year. The first quarter - and possibly beyond -

promises to be difficult with the virus gaining strength across the

world. But the markets will look ahead to the likely recovery given

the rollout of vaccines currently underway.

A significant rise in inflation failed to materialise after QE was

introduced in 2008. The same scenario could play out again in the

coming years, supporting the secular stagnation/Japanification

theory. But if price levels rise - and more importantly,

expectations of prices rise - and this becomes entrenched, then we

could begin to see, finally, a shift in the credit cycle.

Regions with higher corporate leverage and lower economic growth

would inevitably suffer most in the credit markets. Asian debt may

fare better on these terms, but investors with international

exposure to the credit markets should keep a close eye on CDS

spreads for signs of distress and, of course, impending

defaults.

S&P Global provides industry-leading data, software and technology platforms and managed services to tackle some of the most difficult challenges in financial markets. We help our customers better understand complicated markets, reduce risk, operate more efficiently and comply with financial regulation.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.