UCITS: A modern twist or a perilous direction?

Over recent months, fund classification of UCITS has been called into question due to liquidity issues, redemption gates and concerns that there are incentives for fund managers to act outside the spirit of the directive. A particular area of interest has been valuation uncertainty and the liquidity properties of asset that constitute what's sometimes called the 10% "trash bucket", referring to the portion of a fund's assets that can, under UCITS, be invested in illiquid instruments. Given recent spotlight, asset managers need to review their 10% allocations quickly, before their investors or regulators come knocking.

What is UCITS

The Undertakings for Collective Investment in Transferable Securities refers to a series of European Union directives that established a uniform regulatory regime for the creation, management and marketing of collective investment vehicles in the countries of the EU. UCITS is a mutual fund wrapper that emerged in the 1980s and which is readily available to retail investors globally.

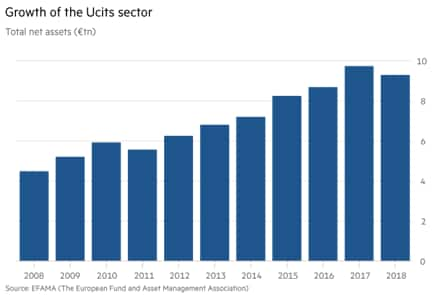

Seen as an international gold standard of fund regulation, the UCITS sector consists of roughly €9.5tn of assets spanning more than 33,000 funds. UCITS is an example of successful European financial integration but in some quarters questions are being raised about this political and economic accord. Some €352bn in assets are held in so-called "Alternative UCITs" funds in Europe which are designed to replicate hedge fund strategies in an instant-access mutual fund format.

UCITS typically invest in securities listed on public stock exchanges and regulated markets. Due to the retail investor audience, UCITS products are generally considered vanilla in nature, operating with embedded investment restrictions and subject to robust regulatory oversight and scrutiny. The UCITS directives have brought European investors a wide offering of funds along with provisions for investor protection. Investors can invest in any UCITS fund that has been registered for sale in their country. Before the first UCITS directive, most investors were largely limited to funds offered by fund companies based in their country of residence. The UCITS directives have thus greatly broadened the choice of funds available to investors in the EU.

Diversification and liquidity

Since UCITS funds are designed to be suitable for retail investors, their rules incorporate certain levels of diversification with the aim of reducing their vulnerability to the performance of a small number of assets. In general, the more diverse the assets in a fund, the less likely it is that investors could lose a substantial portion of their investment if one particular asset falls in value. Furthermore, redemption liquidity is one of the most important characteristics of UCITS.

The most commonly known restriction is the so-called "5/10/40 rule". In summary, this says that a maximum of 10 per cent of a UCITS fund's net assets may be invested in securities from a single issuer, and that investments of more than 5 per cent with a single issuer may not make up more than 40 per cent of the whole portfolio.

There are some exceptions to this rule. For example, where the fund is replicating a stock market or other index, the maximum limit per issuer is 20 per cent of net assets (or 35 per cent in exceptional circumstances).

An individual investment in another UCITS fund must not exceed 20 per cent of assets, while no more than 30 per cent of the UCITS fund's portfolio can be invested in non-UCITS funds. In addition, UCITS funds may not make an investment in another UCITS fund that amounts to more than 25 per cent of the other fund's total assets.

In accordance with the principle of risk-spreading, the regulator of a UCITS may authorise it to invest up to 100 per cent of its assets in securities and money-market instruments issued or guaranteed by EU member states or local authorities (intended to encourage investment in slower-growth EU member states).

But has the hunt for yield over the last decade resulted in some UCITS principles being compromised in sprit?

Liquidity and the evolution of UCITS

Of the five iterations of the UCITS directive, the passage of UCITS III in 2003 was perhaps the most instrumental in giving rise to some of the liquidity concerns that have been expressed by regulators and commentators recently. UCITS III expanded the type of instruments which funds could hold to include investments in OTC (over the counter) derivative instruments and ETD (exchange traded derivatives) for purposes beyond just risk mitigation and hedging.

In the hunt for yield, in a world of ultra-low interest rates, this has pushed some UCITS funds to invest in riskier and less liquid assets (such as unlisted equities and private credit) that comply with the letter of the UCITS directives but may prove tough to sell in a downturn or in an underperforming sector. This creates a risk that the fund will not be able to sell sufficient assets to meet redemption requests from investors.

UCITS and the 10% ratio

Article 50(2)(a) of the UCITS Directive provides the legal underpinning for the 10% illiquid assets ("trash") ratio. Effectively, this 10% can be used for a range of investments including open-ended unregulated hedge funds and Level 3 (illiquid) investments, provided the investment made under Article 50(2) (a):

- Does not compromise the liquidity requirements of UCITS and a fund's ability to comply with its redemption requirements;

- Does not present a risk that the potential loss which the UCITS fund may incur, with respect to holding these instruments, will exceed the amount paid for them;

- Is consistent with the UCITS fund's investment objectives or investment policy;

- Has appropriate information available in the form of regular and accurate information on the security or, where relevant, on the portfolio of the security;

- Has its risks adequately captured by the risk management process of the UCITS fund; and

- Makes reliable valuations available on a periodic basis which are derived from information provided by the issuer of the security or a competent advisory.

Implications for investors

One implication of the 10% ratio is that it increases the risk to investors that a fund might restrict redemptions if it is unable to or unwilling to sell illiquid assets in times of market stress. Europe is not alone in permitting such action. In the US, reforms to Rule 2a-7 under the Investment Company Act of 1940 liberalised the use of gates.

From the fund manager's perspective, imposing a "gate" is reserved for extreme conditions, because in benign market and redemption conditions:

- The illiquid part of the portfolio is a small percentage and they can meet redemptions by disposing of the liquid parts of the portfolio;

- Imposing a gate could damage the Sharpe ratio of the fund (due to the premiums the illiquid assets should exhibit);

- They may have long-standing and loyal cornerstone investors who have stuck with them even during underperformance, so they may feel there is little risk of an increase in redemptions affecting the strategy.

For the investor, the challenge is that these can all be true at a point in time, but all are subject to change at short notice.

When a fund faces higher than usual redemptions, illiquid positions are, typically, not sold down pro-rata and will therefore form a higher relative portion of the portfolio, increasing liquidity risk for remaining investors. There are two reasons for not selling the illiquid holdings:

- Should you sell a sizable holding in an un-listed or thinly traded asset then it will move the market price down and lock in a loss as you're facing a market in which (as your time to unwind shortens) it would be difficult to achieve what could be considered fair-value.

- The rest of your holdings may be marked down too. This leads to further poor performance, causing more investors to worry and request redemptions.

NAV and UCITS valuation

The sale or purchase price for a UCITS fund is determined by the Net Asset Value per share or NAV. NAV is equal to the net assets of the fund divided by the number of shares or units held by investors so pricing and valuation of the assets are clearly important.

For investors to have confidence in a UCITS fund, they must be able to trust the valuations it uses for individual assets and for the NAV. Investors buy shares or units in a UCITS without knowing the exact price, which is only established after the deal has been placed. As a rule, the latest official market closing prices must be used to value publicly-traded securities, otherwise a 'fair market value' must be provided. This is designed to offer protection against late trading, market timing and other practices that can affect the value of a fund.

When a fund contains illiquid assets, it makes the valuation process more complicated and introduces greater subjectivity into the NAV calculation. The fund manager may appoint an outside firm to carry out such valuations. If the manager carries out valuations in-house, the process must be independent of the portfolio management to avoid conflicts of interest.

Improving guidelines for valuing unlisted equities

It's critical to understand that there are benefits from the 10% illiquid ratio in UCITS funds, especially when these investments support long-term and socially beneficial assets such as infrastructure projects and relatively early stage companies. However, as seen on numerous occasions, capturing risk and appropriately valuing assets in such investments may be a challenge for the manager. This matter was recognised by the International Private Equity and Venture Capital Valuation Guidelines Board and in October 2018 a draft revised guidance note was issued by IPEV.The revised IPEV guidance is not prescriptive but does provide the framework which should be considered in assessing the fair value of a company.

The material enhancements to the guidance were to:

- Remove Price of a Recent Investment as a Valuation Technique to reinforce the premise that Fair Value must be estimated at each Measurement Date. This removes the possibility that funds or valuation advisors rely on historical funding data for too long; and

- Expand Valuation considerations for early-stage investments.

Accordingly, valuation and risk policies become extremely important for Level 3 assets. This could be an area which is not given due consideration by UCITS managers (particularly those who don't benefit from independent third party valuations), because the 10% illiquid bucket requires additional levels of controls and verification.

Valuation Considerations for Early-Stage Innovative Companies

When valuing an early stage innovative company, a number of factors should be considered, including:

- The change in market and sector pricing conditions;

- The complexity of the capital structure of the company;

- The recent developments in the underlying technology and innovation of the business and the industry; and

- The timeline and exit plan for the investor.

Due to the difficulty of gauging the probability and financial impact of the success or failure of development activities of early stage companies, one should consider that the traditional valuation techniques cannot be used in all cases.

In their latest draft valuation guidelines, the IPEV and the AICPA recommend the use of more complex valuation methodologies, when necessary. These complex valuation techniques may include:

- Scenario-Based Model (or PWERM);

- Option Pricing Model; or

- Milestone-Based Model (or adjusted price or recent investment).

*For more detail on the IPEV guidelines please see Appendix 1.

It's important to note that the key difference when dealing with Level 3 assets (and particularly early-stage unlisted equity assets) is the heavily analyst-driven approach to valuation. Valuations analysts in such investments must have the aptitude to understand and analyse the legal documentation of the deal, corporate finance theory, financial performance and the relevance of milestones and disclosures, as well as the modelling skills to ensure these are appropriately captured at inception and throughout the life of the deal.

Due to the heterogeneous nature of investments, this requires significant access to the correct market data, research, model infrastructure, people and control oversights. Are the events of the last few months just the start of the debate on the suitability of illiquid investments in mainstream and retail investment funds? Directional change on the fundamental pillars of the investment landscape takes years but scrutiny by investors of the 10% "trash bucket" has already changed materially in just a few weeks due to the perceived change in risk.

However, just the musings of policymakers and regulators (from the Bank of England to the Financial Conduct Authority to ESMA) openly reflecting of the virtues of bank-style stress testing, capital requirements and liquidity testing is sufficient to cause anxiety in the fund industry. At the same time, one needs to recognize the success of the UCITS program and guard against overreaction.

Time will tell, but fund managers have the opportunity now to be proactive in reviewing their valuation methodologies and evaluating their 10% buckets before their investors do!

Appendix 1:

A further look into the IPEV guidelines:

For unlisted equity there are generally accepted industry best practice - the International Private Equity and Venture Capital Valuation Guidelines issues by the IPEV Board, US GAAP and IFRS - incorporating the most widely used methodologies to establish a baseline valuation. The latest text from IPEV Concept of Fair Value states:

1.1 Fair Value is the price that would be received to sell an asset in an Orderly Transaction between Market Participants at the Measurement Date.

1.2 Fair Value measurement assumes that a hypothetical transaction to sell an asset takes place in the Principal Market or in its absence, the Most Advantageous Market for the asset.

1.3 For actively traded (quoted) Investments, available market prices will be the exclusive basis for the measurement of Fair Value for identical instruments.

1.4 For Unquoted Investments, the measurement of Fair Value requires the Valuer to assume the Investment is realised or sold at the Measurement Date whether or not the instrument or the Underlying Business is prepared for sale or whether its shareholders intend to sell in the near future.

1.5 Some Funds invest in multiple securities or tranches of the same Investee Company. If a Market Participant would be expected to transact all positions in the same underlying Investee Company simultaneously, for example separate Investments made in series A, series B, and series C, then Fair Value would be estimated for the aggregate Investment in the Investee Company. If a Market Participant would be expected to transact separately, for example purchasing series A independent from series B and series C, or if Debt Investments are purchased independent of equity, then Fair Value would be more appropriately determined for each individual financial instrument.

1.6 Fair Value should be estimated using consistent Valuation Techniques from Measurement Date to Measurement Date unless there is a change in market conditions or Investment-specific factors, which would modify how a Market Participant would determine value. The use of consistent Valuation Techniques for Investments with similar characteristics, industries, and/or geographies would also be expected.

The latest text from IPEV Principles of Fair Value states:

2.1 The Fair Value of each Investment should be assessed at each Measurement Date.

2.2 In estimating Fair Value for an Investment, the Valuer should apply a technique or techniques that is/are appropriate in light of the nature, facts, and circumstances of the Investment and should use reasonable current market data and inputs combined with Market Participant assumptions.

2.3 Fair Value is estimated using the perspective of Market Participants and market conditions at the Measurement Date irrespective of which Valuation Techniques are used.

2.4 Generally, for Private Capital Investments, Market Participants determine the price they will pay for individual equity instruments using Enterprise Value estimated from a hypothetical sale of the equity which may be determined by considering the sale of the Investee Company, as follows:

- Determine the Enterprise Value of the Investee Company using the Valuation Techniques;

- Adjust the Enterprise Value for factors that a Market Participant would take into account such as surplus assets or excess liabilities and other contingencies and relevant factors, to derive an Adjusted Enterprise Value for the Investee Company;

- Deduct from this amount the value, from a Market Participant's perspective, of any financial instruments ranking ahead of the highest-ranking instrument of the Fund in a sale of the Investee Company;

- Take into account the effect of any instrument that may dilute the Fund's Investment to derive the Attributable Enterprise Value;

- Apportion the Attributable Enterprise Value between the Investee Company's relevant financial instruments according to their ranking;

- Allocate the amounts derived according to the Fund's holding in each financial instrument, representing their Fair Value.

2.5 Because of the uncertainties inherent in estimating Fair Value for Private Capital Investments, care should be applied in exercising judgement and making the necessary estimates. However, the Valuer should be wary of applying excessive caution.

2.6 When the price of the initial Investment in an Investee Company or instrument is deemed Fair Value (which is generally the case if the entry transaction is considered an Orderly Transaction), then the Valuation Techniques that are expected to be used to estimate Fair Value in the future should be evaluated using market inputs as of the date the Investment was made. This process is known as Calibration. Calibration validates that the Valuation Techniques using contemporaneous market inputs will generate Fair Value at inception and therefore that the Valuation Techniques using updated market inputs as of each subsequent Measurement Date will generate Fair Value at each such date.

2.7 Valuers should seek to understand the substantive differences that legitimately occur between the exit price and the previous Fair Value assessment. This concept is known as Backtesting. Backtesting seeks to articulate:

- What information was known or knowable as of the Measurement Date;

- Assess how such information was considered in coming to the most recent Fair Value estimates; and

- Determine whether known or knowable information was properly considered in determining Fair Value given the actual exit price results.

S&P Global provides industry-leading data, software and technology platforms and managed services to tackle some of the most difficult challenges in financial markets. We help our customers better understand complicated markets, reduce risk, operate more efficiently and comply with financial regulation.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.